はじめに

今回は、イナゴが大繁殖する仕組みと脅威についての動画を視聴した。調べてみると、北米では13年や17年という素数年数の周期ゼミが周期的に大繁殖することも知った。昆虫食が食糧問題を救うという話もある。昆虫は脅威なのか神秘なのか。関心のある人は動画を視聴してみてほしい。

(出典:YouTube)

蝗と飛蝗

今回の動画はイナゴ(蝗:locusts)の大繁殖の脅威を示したものだけど、イナゴとバッタ(飛蝗:grasshoppers)は似て非なるものだ。最近は、昆虫食が話題になるけど、イナゴとバッタでは味も全く異なるようだ。自分は食べたことがないけど、イナゴはほどよい甘さがあり、佃煮にすれば充分においしく味わえるようだ。一方、バッタは苦みばかりが口に残り、はっきり言っておいしくないようだ。

(出典:Food Tec Info)

イナゴの大繁殖

砂漠では突然イナゴが大繁殖することがある。なぜ突然大繁殖するのだろう。そのポイントは水だった。つまり、普段の砂漠では、イナゴは孤独な生活を送っている。しかし、ある地域に大量の雨が降るとその光景が一変する。イナゴの寿命は3ヶ月ほどだけど、大量の雨が降り、砂漠に緑が復活するとイナゴが指数関数的に繁殖し続ける。典型的なイナゴの大群は、地球上の人間の数よりも多く、数百平方キロメートルの範囲をびっしりと覆う。イナゴの大群は1日に150キロメートルも移動することができ、1988年には大西洋を横断した例も確認されている。イナゴは筏を組んで夜間に休息し、朝には死んだ仲間を栄養源とする朝食をとる。陸上では湿った土を探し、卵を産む。群れを作る母親は、その群れの状態を子供に移し、次の世代がまた群れを作る。

(出典:明峰コミュニティ協議会)

孤独相と群生相

乾燥地域の孤独(solitary)なイナゴは、砂漠の土の中に産みつけられ、成長すると、地上に出て、繁殖し、死んでいく。しかし、大量の雨が降ると、食糧の増大に伴って大きな群れになり、大きな群れの中でイナゴの足毛が刺激されるとホルモンが分泌され、さらに群れをなして活発に活動するようになる。さらに、大蜀漢のイナゴが排出する便にはイナゴの変身を促すフェロモンが含まれている。イナゴは毎週のように脱皮を繰り返し、1ヶ月で孵化時の50倍まで成長する。最後に鮮やかな色彩を放つイナゴに成長すると、半透明な羽を打ち鳴らし、イナゴの大群として飛び立つ。このように群生するイナゴは単独で行動するイナゴと別種と考えられていたが、今では大雨が契機で孤独相から群生相に切り替わることが判明した。

周期ゼミの神秘と脅威

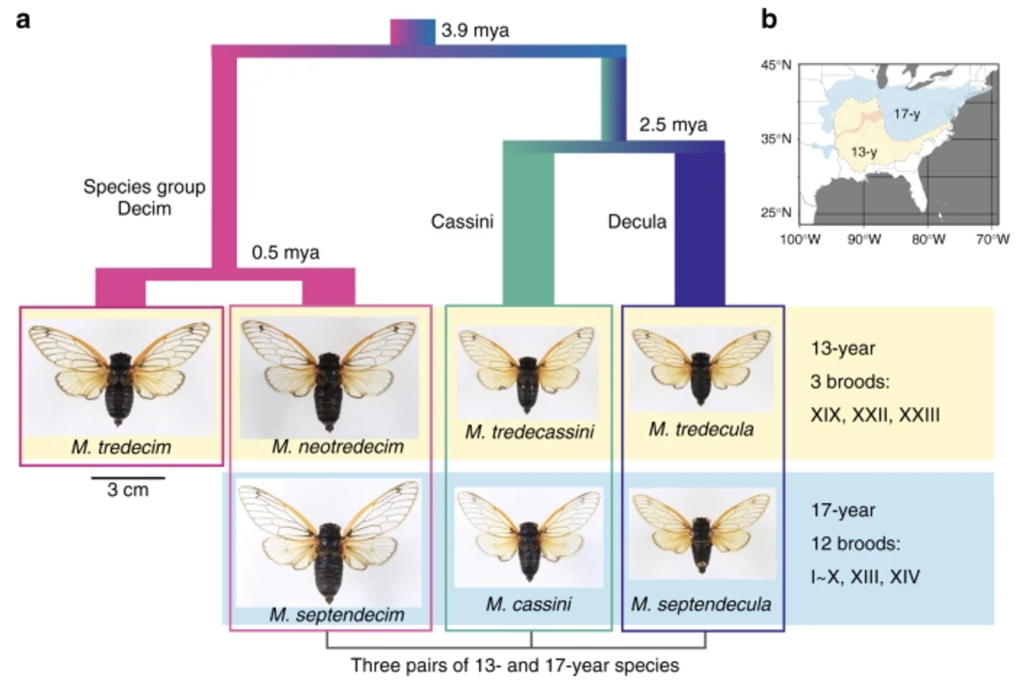

大繁殖するのはイナゴだけではない。例えば北米には、下の図のaに示すように、13年周期と17年周期のセミ(蝉:cicada)がいる。地中の中に13年や17年も眠り、タイミングになると一斉に孵化する。13年と17年はそれぞれ素数なので、13×17=221年周期だ大繁殖が重なり合うことになる。また、興味深いのは下の図のbに示すように、13年周期ゼミと17年周期ゼミの分布範囲が異なっていて、棲み分けしていることだ。

(出典:Nature)

10の質問

Q1) What do scientists call the two phases of locusts?

イナゴの2つの相を科学者は何と呼んでいるかという設問だ。孤独相と群生層なので、「solitary and gregarious」が正解か。

Q2) What cues do locusts uses to determine their population density?

イナゴはどのような合図で生息密度を判断しているのかという設問だ。脚の毛の刺激や糞のにおいなどなので、「The stimulation of leg hairs and the smell of feces」が正解か。

Q3) How many kilometers (miles) can a locust swarm travel in a day?

イナゴの大群は1日に何キロメートル移動できるのかという設問だ。150kmはすごい。

Q4) When a swarm was crossing the Atlantic Ocean, what did the locusts use for food?

イナゴの大群が大西洋を渡っていた時、イナゴは何を食料にしていたのかという設問だ。溺死した他のイナゴなので、「Other locusts that had drowned」か。

Q5) What human practices lessen the predictability and increase the severity of locust plagues?

イナゴの大発生を予測しにくくし、大発生させやすくしているのはどのような人間の営みかという設問だ。気候の変化と均一な作物の植え付けが誘起しているので、「Changing the climate and planting uniform crops」か。

Q6) How long can a locust plague last?

イナゴの疫病はいつまで続くのかという設問だ。これは難しかったけど、最長で10年なので、「Up to 10 years」か。

Q7) What methods are typically used to control locust swarms?

イナゴの大群を駆除する方法として一般的にどのようなものがあるかという設問だ。化学殺虫剤やカビ病菌の散布なので、「applying chemical insecticides and fungal diseases」か。

Q8) To control locust swarms, people rely heavily on chemical insecticides. What are two reasons why this approach makes sense and two reasons why this strategy is not optimal? Given your answers, what would be the potential advantages and disadvantages of using insect diseases spread by aircraft to control locusts?

イナゴの大群を駆除するために、人々は化学的な殺虫剤に大きく依存している。この方法が理にかなっている理由を2つ、この方法が最適でない理由を2つ教えてください。また、航空機で拡散する昆虫病を使ってイナゴを防除する場合、どのようなメリットとデメリットが考えられますかという設問だ。理にかなっている理由はイナゴの大群を防除でき、緑地や環境を維持できることであり、一方、化学殺虫剤を使用するため、殺虫剤の影響が出る可能性があること、有害性が保てないことなどがある。防虫剤の利点と欠点は、食料と環境を守れることと、健康に影響があることですと考えたので、英文で言えば次のような感じか。

Q9) Planting a single kind of crop is called a “monoculture” and this agricultural strategy has been found to worsen pest outbreaks. Why would large-scale plantings of a uniform variety be more susceptible to insect pests—and why do you think that farmers use this approach if it makes for more pest problems?

単一品種の作物を植えることを「モノカルチャー」と言う。この農業戦略は害虫の発生を悪化させることが分かっています。均一な品種の大規模な植え付けは、なぜ害虫の影響を受けやすいのか。また、害虫の問題が多くなるのであれば、なぜ農家はこの方法をとるのかと言う設問だ。植え付けに、モノカルチャーは畑のバランスを欠く原因になる。しかし、モノカルチャーを行う理由は、経済的な方法に基づいています。農家は効率と持続可能性に悩んでいるので、英語で言えば次のような感じか。

Q10) Locusts undergo dramatic changes in their physiology, anatomy, and behavior when they become crowded. What other animals exhibit biological changes as their population densities increase and what are the biological effects of these transformations?

イナゴは群れをなすと生理・解剖・行動に劇的な変化を起こす。他にどのような動物が個体数の増加に伴って生物学的な変化を示し、その生物学的効果はどのようなものかと言う設問だ。

ヘビにも変態の生物学的効果を見出すことができるので、次のように回答した。ただ、よく調べると周期ゼミもあった。これは前述の通りだ。

まとめ

イナゴの大繁殖は、聞いたことはあるけど、砂漠で起きているとは知らなかった。その原因が大雨ということで、地球の温暖化とセットで解説する人がいる一方で、池田清彦は著書「環境問題の嘘、令和版」において、過去にもバッタの大量発生は起きていて地球の温暖化が原因とは断定できないようだ。ただ、メカニズムが明確なので、イナゴを大量に必要になったら、イナゴを密集した場所にたっぷりの食料と共に飼育すると一斉に発生することになる。でも、本当にイナゴは食べられるのか、食べて美味しいのか。

以上

最後まで読んで頂き、ありがとうございました。

拝

参考:英文スクリプト

The ravenous swarm stretches as far as the eye can see. It has no commanding general or strategic plan; its only goals are to eat, breed, and move on – a relentless advance that transforms pastures and farms into barren wastelands. These are desert locusts(イナゴ) – infamous among their locust cousins for their massive swarms and capacity for destruction. But these insects aren’t always so insatiable. In fact, most of the time desert locusts are no more dangerous than garden-variety grasshoppers(バッタ). So what does it take to turn these harmless insets into a crop-consuming plague? Desert locust eggs are laid in the damp depths of desert soil, in arid regions stretching from North Africa to South Asia. During the dry weather typical in these ecosystems, desert locusts live a solitary (孤独な) lifestyle. Adolescent hoppers will spend a few lonely weeks foraging for plants, before growing wings, reproducing, and dying. But when a region receives an abundance of rain, the scene is set for a startling transformation. Increased moisture supports more vegetation for newly hatched hoppers to eat, leading large groups to feed in close proximity. The frequent contact stimulates their leg hairs, triggering the release of a hormone that causes them to actively cluster even closer.

Gluttonous crowds of locusts produce huge amounts of poop, which carries a pheromone that furthers their transformation. The hopper’s diet shifts to include plants with toxic alkaloids. Soon, the locusts take on a striking pattern that warns predators of their newly poisonous nature. Smaller groups merge into bands of millions, which mow down virtually all plant life in a kilometer-wide swath. Roughly every week they shed and expand their exoskeletons, growing to roughly 50 times their hatching weight in just one month. Finally, the metamorphosis is complete. The adults beat their translucent wings and take flight as a full-fledged locust swarm. In this gregarious phase, these long-winged, brightly colored creatures appear so different from the solitary counterparts that they were long thought to be a separate species. A typical swarm contains more locusts than there are humans on the planet, covering hundreds of square kilometers in a dense cloud. At these numbers, desert locusts easily overwhelm their predators. A large swarm can match the daily food intake of a city of millions, and flying with the wind, the insect invasion can travel up to 150 kilometers a day.

This living tornado can also cross large bodies of water. In 1988, a swarm even managed to traverse the Atlantic Ocean. The locusts likely formed rafts to rest at night, before fueling up in the morning with a nourishing breakfast of their dead kin. While flying over land, they seek out moist soil to lay eggs. Swarming mothers transfer their gregarious condition to their offspring, making it likely that the next generation will form another swarm. This means that while an individual desert locust lives only three months, a plague can last up to a decade. The potential for a yeas-long plague isn’t unique to desert locusts, but the region they inhabit makes the prospect particularly deadly. Their habitat spans some of the world’s poorest countries, largely populated by people who grow their own food. By consuming crops and pastures, these insects directly endanger 10% of humanity.

Fortunately, a desert locust plague doesn’t last forever. When a wet period ends, the vegetation becomes scarce and egg-laying conditions decline. As existing swarms die off, new hatchlings spread out in search of food, creating enough distance to prevent solitary locusts from transforming. Human intervention can also help. Researches use satellite imagery to identify regions at risk of becoming locust hotspots and alert local governments. While most countries fight back with chemical insecticides, some regions have found success using fungal diseases that are lethal to locusts but safe for people and the environment. Unfortunately, other modern practices are exacerbating the threat. Fields densely packed with a single crop are like a table set for locusts. And erratic weather caused by climate change makes swarms harder to predict. If we plan to discourage lonely locusts from becoming catastrophic crowds, humans need to cut carbon emissions, rethink our agriculture, and generally reconsider our own ravenous appetites.