はじめに

1兆本の木というタイトルに目が行き、今日はこれを視聴することにした。しかし、なかなか難解だった。特に字幕なしで英語のみで聴いているとつい睡魔に襲われ、意識が何度か飛んでいった。英語の字幕をつけると少しマシだった。日本語の字幕ではそういうことかと目から鱗だった。やはり英語を英語で理解する脳がまだまだできていないことを実感した。そんな英語脳を育てたい人はぜひトライしてほしい。

(出典:TED-Ed)

シャーマン将軍

米国カリフォルニアには、樹齢2200年、高さ83.8m、円周31.1メートルのシャーマン将軍の木(General Sherman)がある。世界最古の原生する木は同じく米カリフォルニアのホワイトマウンテン図に生息する。推定年齢は2022年時点では4,853年となる。屋久島の上屋久町小杉谷の標高1300メートル地点で、樹高30m、根廻り43mの縄文杉が発見されている。推定樹齢は7,200年なので、こちらこそが世界最古の植物ではないのだろうか。

(出典:Secret World)

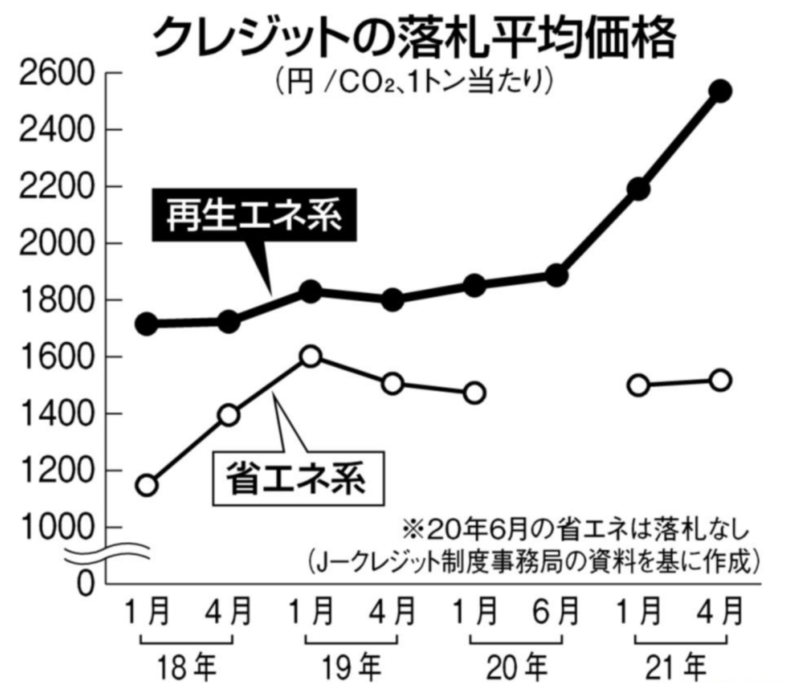

二酸化炭素のクレジット

これは動画にはなかったけど、CO2クレジットの価格が高騰している。CO2クレジットとは、排出権取引(Emissions trading)のことで、京都議定書の第17条に規定された温室効果ガスの削減を補完する京都メカニズムの一つだ。国や企業ごとに温室効果ガスの排出枠を決めて、CO2の排出枠をお金で生産する仕組みだ。二酸化炭素1トン当たり2600円という。人類は毎分2,400トン以上の炭素を生産しているので、CO2ビジネスとしては、年間3.3兆円の市場となる。環境ビジネスが胡散臭く感じるのは、このようにビジネスに直結しているためだ。

(出典:日刊工業新聞)

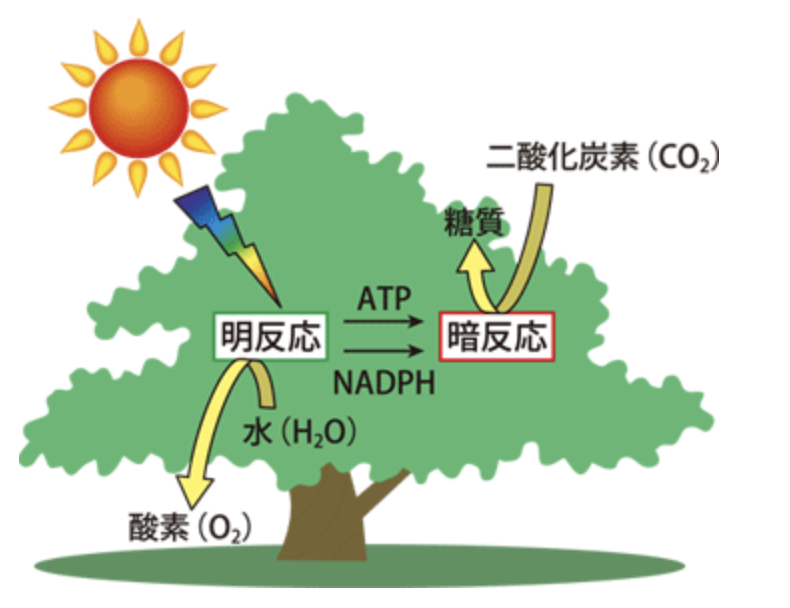

樹木による光合成

光合成の仕組みは中学や小学校で習う。二酸化炭素(CO2)と水(H2O)と太陽の光で酸素(O2)を作り出す。でも残った炭素(C)と水素(H)はどうなるのか。分子構造から言えばメタン(CH4)が生成できそうだけど、そんなことは教科書には書かれていない。樹木の場合には、生成された炭素は放出され図に、木の組織として蓄えられ、成長する限り炭素を取り込むという。では、残る水素(H)はどうなるのだろうい。下の図に示すように明反応と暗反応により糖質を生成するようだ。自然の仕組みは素晴らしい。

(出典:Spring8)

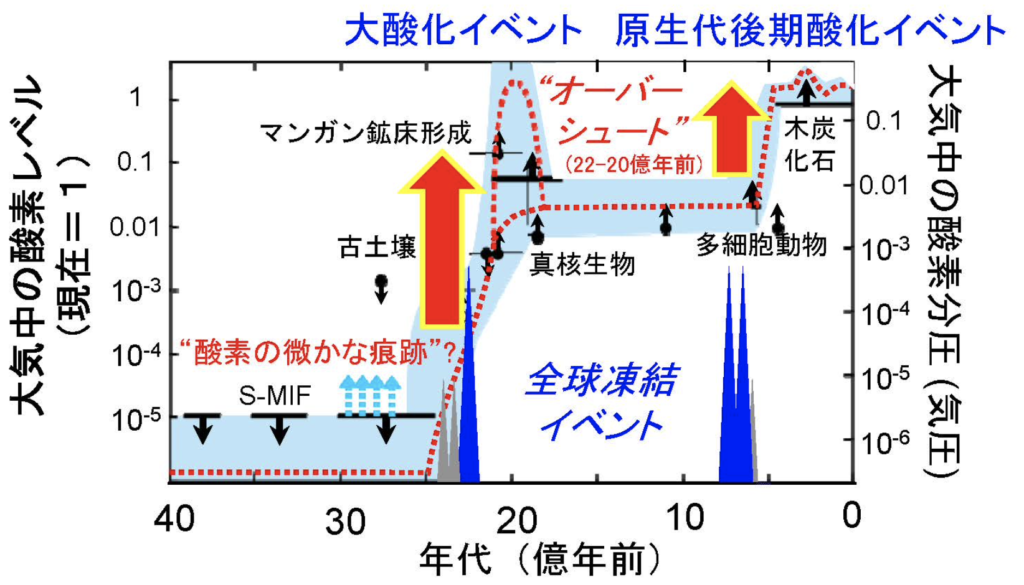

二酸化炭素の増大阻止と酸素の減少阻止

地球上の酸素はなんと約1,200兆トンだという。一方、植物などの光合成で生成される酸素の量は年間で2,600億トンだ。つまり、4615年ほどで地球の空気(酸素)が一巡する。これは個人的な感覚だけど、本当にやばいのは二酸化炭素の増大よりも、酸素の生成量の現象なのではないだろうか。そもそも地球は10万年単位で氷河期と温暖な時期を繰り返している。温暖な時期はごくわずかでほとんどが氷の世界だ。温室効果ガスで温暖な時期が伸びるという側面もある。酸素濃度は、下の図のように、太古の時代からは植物の繁栄により増大するが、20億年まえに現在のレベルに達した後に1-2億年かけて現在の100分の一に低下するという「酸素濃度のオーバーシュート」が発生している。産業革命に伴い大量の化石燃料の消費が続いている。大気中の酸素濃度は約21%だけど、大気中の酸素濃度は減少している。現在の減少率が続くと5000年後には息苦しさを感じる18%まで減少する。これは大きな問題だと思う。CO2の排出量を減らすために、森林を伐採して、メガソーラを建設することが本当に自然環境の保護になるのか。逆に自然破壊を加速することになるのではないかと強く危惧する。地球温暖化ガスの抑制の意義を否定するつもりはないけど、なぜそれよりも酸素の減少の阻止を問題視しないのだろう。高血圧の弊害は煽って降圧剤を大量に販売するけど、低血圧の弊害はスルーする構造と似ている印象を受けてしまう。

(出典:田近研究室)

10億ヘクタールの森林追加

スイスのチューリッヒ工科大学の生態学のトーマス・ワードクラウザー教授(Thomas Ward Crowther、1986年生)は、生態系の回復に関する国連の10年の諮問委員会の共同議長である。クラウザー教授が地球の気候を調節する上での生物多様性の役割を探求する科学者の学際的グループであるCrowther Labを立ち上げた。同Labは、2019年に地球は約10億ヘクタールの森林を追加することで支えられるという計算結果を報告した。約1兆2,000億本の木に相当し、人類が排出する炭素は約6分の1に相当する1000億トンから2000億トンの炭素を吸収する。2011年に発足したボン・チャレンジでは、2020年までに世界で1億5000万ヘクタールの森林を再生するという目標を上方修正し、2030年までに3億5000万ヘクタールの森林を再生することを目標と掲げている(参考)。

(出典:Science)

人間に自然は必要。でも自然に人間は必要としない。

環境ビジネスでは、よく「地球にやさしい」という表現を使うけど、これにも抵抗感がある。地球はもっとタフだ。CO2が増えようが酸素が減ろうが地球は困らない。困るのは人類だ。そして、CO2を増やしているのも、酸素を減らしているのも人類だ。人類は自然と共に生きているので、自然が不可欠だけど、自然は人類を必要としているわけではない。人類は謙虚に自分の存在意義を見つめ直し、地球の中で他の生態系と共存するための知恵を絞る必要がある。知恵を絞ると言っても太古の時代には、自然とともに生きていた。太古に戻ることはできなけど、太古から学ぶことはできる。

(出典:congrant)

まとめ

木の乾燥重量の約50%は炭素で構成されている。植物も呼吸をしている。光合成をするのは昼まであって、夜はCO2を排出している。好きなテレビ番組「ほんまでっか」で寝室には観葉植物を置かない方が良いと言っていたのはそういう意味だ。生態系は複雑系だ。その地域で昔から生えている植物を植えるべき。自然の復元には、適切な場所に適切な樹木を植える。固有種の再成長を促す。生態系を保護する。生態系を監視する。気候変動と社会経済的側面を考慮した生態系の持続可能性を確保する。地域コミュニティの参加する。これらすべての対応が求められている。

以上

最後まで読んで頂きありがとうございます。

拝

参考(英文スクリプト)

Standing at almost 84 meters tall, this is the largest known living tree on the planet. Nicknamed General Sherman, this giant sequoia has sequestered roughly 1,400 tons of atmospheric carbon over its estimated 2,500 years on earth. Very few trees can compete with this carbon impact, but today, humanity produces more than 2,400 tons of carbon every minute. To combat climate change, we need to steeply reduce fossil fuel emissions, and draw down excess CO2 to restore our atmosphere’s balance of greenhouse gases. But what can trees do to help in this fight? And how do they sequester carbon in the first place? And how do they sequester carbon in the first place? Like all plants, trees consume atmospheric carbon through a chemical reaction through a chemical reaction called photosynthesis. This process uses energy from sunlight to convert water and carbon dioxide into oxygen and energy-storing carbohydrates.

Plants then consume these carbohydrates in a reverse process called respiration, converting them to energy and releasing carbon back into the atmosphere and releasing carbon back into the atmosphere. in trees, however, a large portion of that carbon isn’t released, and instead, is stored as newly formed wood tissue. During their lifetimes, trees act as carbon vaults(保管庫), and they continue to draw down carbon for as long as they grow. However, when a tree died and decays, some of its carbon will be released back into the air. A significant amount of CO2 is stored in the soil, where it can remain for thousands of years. But eventually, that carbon also seeps back into the atmosphere. So if trees are going to help fight a long-term problem like climate change, they need to survive to sequester(隔離) their carbon for the longest period possible, while also reproducing quickly. Is there one type of tree we could plant that meets these criteria? Some fast-growing, long-lived, super sequestering(貯留) species we could scatter worldwide?

Not that we know of. But even if such a tree existed, it wouldn’t be a good long-term solution. Forests are complex networks of living organisms, and there are no one species that can thrive in every ecosystem.

The most sustainable trees to plant are always native ones. species that already play a role in their local environment. Preliminary research shows that ecosystems with a naturally occurring diversity of trees have less competition for resources and better resist climate change.

This means we can’t just plant trees to draw down carbon; we need to restore depleted ecosystems. There are numerous regions that have been clear cut or developed that are ripe for restoration.

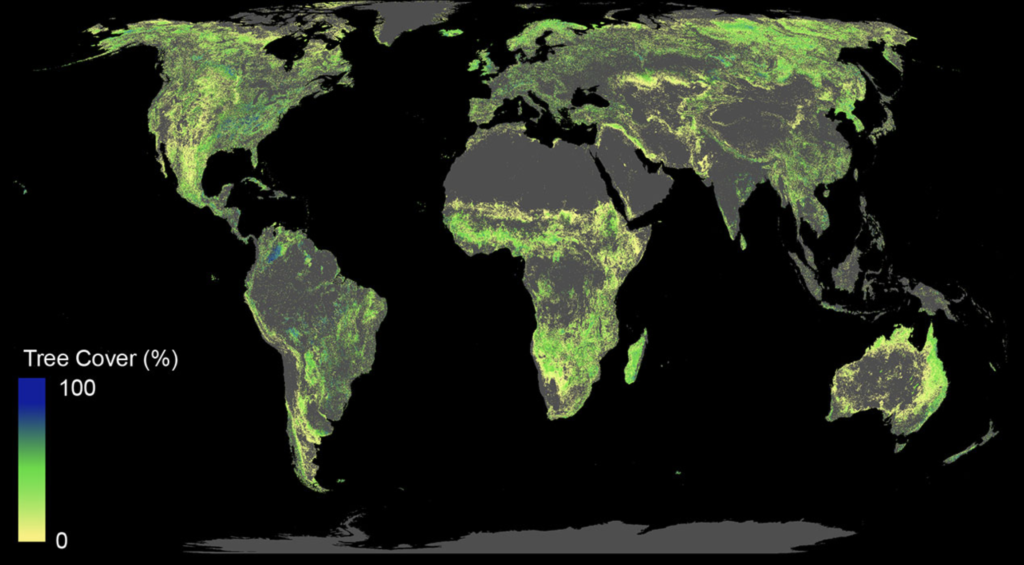

In 2019, a study led by Zurich’s Crowtherlab analyzed satellite imagery of the world’s existing tree cover. By combining it with climate and soil data and excluding areas necessary for human use, they determined Earth could support nearly one billion hectares of additional forest.

That’s roughly 1.2 trillion trees. This staggering number surprised the scientific community, prompting additional research. Scientists now cite a more conservative but still remarkable figure. By their revised estimates, these restored ecosystems could capture anywhere from 100 to 200 billion tons of carbon, accounting for over one-sixth of humanity’s carbon emissions.

More than half of the potential forest canopy for new restoration efforts can be found in just six countries. And the study can also provide insight into existing restoration projects, like The Bonn Challenge, which aims to restore 350 million hectares of forest by 2030.

But this is where it gets complicated. Ecosystems are incredibly complex, and it’s unclear whether they’re best restored by human intervention. It’s possible the right thing to do for certain areas is to simply leave them alone.

Additionally, some researchers worry that restoring forests on this scale may have unintended consequences, like producing natural bio-chemicals at a pace that could actually accelerate climate change. And even if we succeed in restoring these areas, future generations would need to protect them from the natural and economic forces that previously depleted them.

Taken together, these challenges have damaged confidence in restoration projects worldwide. And the complexity of rebuilding ecosystems demonstrates how important it is to protect our existing forests.

But hopefully, restoring some of these depleted regions will give us the data and conviction necessary to combat climate change on a larger scale. If we get it right, maybe these modern trees will have time to grow into carbon carrying titans.